- Home

- Caleb J. Ross

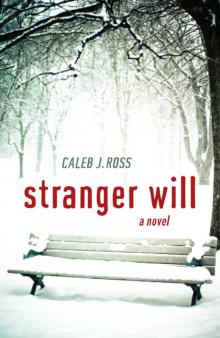

Stranger Will

Stranger Will Read online

Praise for

Stranger Will: a novel

“Just like a Palahniuk novel, Stranger Will reads volatile: it could go any way. Caleb J. Ross leads you with a wry smile into dark places, but by the time you realize it’s too late. You will follow him anywhere.”

Alan Emmins, author of Mop Men: Inside the World of Crime Scene Cleaners

“As someone who teaches, edits and reads for a living, I’m always looking for the scene, the character, the story I haven’t read a thousand times over and over. Something with the spark of originality and the courage to be different…And, thanks to Caleb J. Ross and his Stranger Will, I had those moments of joy repeatedly throughout the book. This is an original—unlike anything you’ve ever read before.”

Rob Roberge, author of More than they Could Chew and Working Backwards from the Worst Moment of my Life

“Stranger Will is a nightmare landscape littered with the carcasses of fatherhood and various social mores. This is one paranoid, challenging, beautiful, and pitch-dark book. I’m a little afraid of this Ross guy now; but I’ll also read anything he writes.”

Paul Tremblay, author of The Little Sleep and In the Mean Time

“With ease, Ross seems to dare you to turn the page…His writing is fearless. The courageous reader will not be dissatisfied.”

Kristin Fouquet, author of Twenty Stories and Rampart & Toulouse

Stranger Will:

a novel

Caleb J. Ross

Winchester, UK

Washington, USA

First published by Perfect Edge Books, 2013

Perfect Edge Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK

[email protected]

www.johnhuntpublishing.com

www.perfectedgebooks.com

For distributor details and how to order please visit the ‘Ordering’ section on our website.

Text copyright: Caleb J. Ross 2012

ISBN: 978 1 78099 806 0

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of Caleb J. Ross as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design: Stuart Davies

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

CONTENTS

IN UTERO

BREECH

A VERSION

APPENDIX

For Jameson. I couldn’t have written this book with you.

IN UTERO

Chapter One

William Lowson had seen a homeless man once before. This was back in Herman Essex, before moving to Brackenwood, before the pregnancy. Even before Julie. William figured him to be just a man with different tastes in clothing, a man like F. Lowson, William’s father, with his thin shirts and pants painted in oil and puddle water. But for that assumption, William was corrected. “That’s not a man,” F. Lowson told his son that day many years ago. “That is a bum.”

The bum hurled a dime, connected with F. Lowson’s neck. The father beat the bum, cursed him as the ambulance drove away, for making his taxes pay the impending hospital bill. Tiny William learned that day that some people are fit for fatherhood, and some aren’t.

An army of homeless claims the streets of Brackenwood.

They march in Salvation Army boots to the tune of secret voices, and chew MREs found in trash bins. They beg for change like their lives are judged at the end of bayonet. But all with white teeth. Clean hair, too. The bums of F. Lowson’s age barely had teeth or hair at all, and here these people were, like catalog model homeless, not an honest stereotype among them.

William had moved his fiancée to Brackenwood just months ago citing its high death rate as promise to a more lucrative life. He removed stains for a living, those left by dead bodies—from roads, from homes, from ditches. From schools, from church pews, from benches. Just the dying homeless alone—encouraged by disease, cold winters, and neglect—William thought would be enough to keep his growing family fed. Though food wasn’t his initial concern after recently learning of Julie’s pregnancy. Instead, he worried about contamination.

The phenyl lacquered into his fingerprint crevasses warps every bite of food into fire. Julie makes a strong goulash, but onion and paprika cannot mask the taste of chemicals used to absolve blood and skin from highways and dashboards. She can ferment a stiff sauerkraut, but even cabbage brine tastes like water when chased with residual Thermo-55 deodorizer.

He’s read every book available at the modest Brackenwood library, searching for a reason to believe that this child could survive beyond these chemicals. The olfactory lobes form as early as six weeks, he’s read. He didn’t know this until week ten when Julie finally revealed her pregnancy. By that time he’d already been inadvertently bathing the fetus in fumes he’d neglect washing from his clothes, instead letting them contaminate the air, fall into Julie’s mouth, down her throat, and into the amniotic fluid flowing through the fetus’s oral and nasal cavities. Biologists used to believe that smell depended on access to air. Now, they could blame William should anything happen. They could blame the bodies he cleans from the road as the source of his child’s imperfections.

“Stay away,” Julie says when William steps into the living room. “You smell like formaldehyde.” He smells chili on the stove, seasoned with the Virex TB cleaner wafting from his shirt.

With each chemical breath William dreams the inhaled fumes were formaldehyde, solidifying his insides, making him capable of just a few more years, a reason to think he could mutate his genes to give any children a few more days than God could.

He loves the baby already. He’s a realist, though. The child, he loves. The idea of a child, he’s beginning to understand, is where everything will go wrong.

He sleeps that night on the living room couch next to the phone. People seem to die a lot in the middle of the night.

Chapter Two

William saunters through the mudroom door, the engine of his bioremediation cleaning van still ticking in the driveway. He flicks a spent cigarette filter deep into the weeds overtaking the house’s north wall. Seen through romantic eyes the abode could be a cottage, but William suffers from universal practicality, a detriment he acknowledges, but only in private. It’s a home, just a building, a refuge maybe, inside which he sleeps and eats.

The cold living room air around him bends by the fumes from his clothes. He removes his shirt, kicks off his shoes, and pulls wet socks from his feet. He tosses the entire bundle into the corner of the living room just feet from Julie’s contorted face. “The bathroom,” she says, needing no other direction. William has dropped his chemical-soaked clothes on the floor enough times to bypass this daily confrontation, but he remains convinced that, yes, changing the routine this late into their pregnancy might subdue guilt, but only for the passing breath. With resentment, he collects the soaked clothes and carries them to the bathroom, his discontent disturbing his already arrhythmic pulse. Slow breaths, he tells himself.

He returns to the living room and drops to the couch. The fabric’s imbedded vapors cool his skin, raise goose bumps and a quick shiver. Julie tosses him an accusatory glance, dismissing his drama. He absorbs the look and returns with a cold stare straight into Julie’s womb.

It has no face, no permanent name. No morals, no beliefs. No idea. It exi

sts tucked beneath Julie’s skin, already a malcontent. Preconception, he calls it. The word makes him laugh. Even preconception the child has no chance. Julie pulls a red-threaded needle through a white cloth, humming a dirge lullaby.

Seven months and twenty-six days and already Julie has decided against adoption. Though no child at all was William’s first choice, adoption would at least pass the burden to a capable couple.

“No eyes?” William says. “Or what if it has extra parts?” Needle in. Needle out.

“What if it, within the first few weeks, shows interest in pointed objects and knows how kitchen drawers work?” he asks. “You are a deep sleeper,” he reminds her, but she continues to handle her needle and thread with precision.

Julie is proud of her role as the tough Lowson, always has been. Diets don’t work for William. Pacing himself with indulgences always ends in a countdown: two weeks and I can eat a brownie. Three days and I have proven to Julie that I don’t need a cigarette. Once, after an argument over his smoking Julie decided to start only to prove that she could quit. Two years and one ambitious addiction later she stopped mid-cigarette, staring at William for effect as she flattened the butt into an ashtray, knuckles white, her grin stretched. William admires her will power, though he could do without her drive to use it against him.

“What if it’s born with seven fingers?” he asks. “Jutting from its face.”

“Then we’ll love it even more,” is always her answer. Spoken in the collective we, the way a teacher might instruct first grade students on the broader points of morality; love good, indifference bad.

Julie has settled on keeping this child and nothing William could say would convince her to avoid clothes shopping and garage sales. Nothing could close her book of names—Regis for a boy, Sarah for a girl. Once, William asked her about neutral names, hermaphroditic possibilities; her cheeks flexed. William braced himself for contact, hoping to receive a slap hard enough to provoke legal questions regarding his ability to care for a child. In his head, the option gained better traction each day. But, she calmed.

This was after a failed meeting with an adoption agent Julie agreed to only if it would settle William’s concerns. He continued, however, using magazine articles, newspaper headlines, tabloid clippings, medical journals, and bar graphs all supporting his theories regarding the eminent turmoil associated with “bringing a child to term in a world like ours.”

“We can’t do this,” he told her. “Someone else can. We shouldn’t do this.”

After seven months and twenty-six days, Julie confidently displays her mastery of composure: “We will.”

She was a waitress when they met, well-acquainted through Sunday afternoon buffets and Monday night breakfast platters. He would watch her flirt with truckers. He believed she had a plan. She would fill her apron with tips and phone numbers, filtering the latter into a small wastebasket below the cash register. After weeks of fabricated attempts, he finally managed eye contact like it was accidental. They pretended brief touching didn’t mean anything. They ate meals at rival restaurants. They fell in love. They got pregnant.

“Seven months and twenty-six days,” William says to Julie. She sits in their abused family-heirloom recliner, cross-stitching, the same as her mother and grandmother did before her. “That’s not enough time to make up your mind about something you’ve never seen.” He grabs a clean shirt from a pile at the foot of the couch.

“It wouldn’t make any difference, William.” She starts the final stroke of an ‘M’. “It’s inside me. We’ve bonded.”

This is an every morning routine. Having quit her job in quality assurance along the factory line of Merling Auto Parts, citing the move to Brackenwood and back problems—the combination of her pregnancy and large frame—Julie sits at home and collects money. Not enough, but William’s smoking and her entertainment for the now lax afternoons are covered. They call her disability checks “the vice fund.” One of the few inside jokes they still have, the only they share with equal enthusiasm. “Remember Paul,” William says. “He was in me. I thought I liked him.”

“Paul was a tapeworm,” she says.

“And ugly. But you can’t say I’m not better off without him.” “The comparison makes no sense,” she says.

“We needed each other, Julie.” William pulls on clean pants. “You didn’t need that thing. It was a parasite.”

“It used me and I couldn’t have imagined life without it.” “Parasite,” she reiterates starting the second stroke of an ‘E’.

“Your need was a mental thing.” “And the child?” he says. “What about the child?”

“Just a parasite, Julie,” he takes a sip of coffee, cold but he keeps his face straight. “Tapeworms, children, we could all use fewer of them.”

“Ungrateful shitheads, too” she adds.

When Julie first moved in, William’s house shifted from his heaven to their starting off point. Julie would talk about his home as though it existed only as temporary, that them living there was a way to save for something bigger. “A home we could grow into,” she had said. Now in Brackenwood they live in their second home, one Julie still refers to as a starter.

It was William who cared enough to fake optimism. It was William who pretended to care about the color of the nursery, who smiled when Julie smiled as her stomach stretched t-shirts and waistbands. And it was William who cared enough to reveal his cynicism, to admit that a child doesn’t deserve what little they can give it. Julie didn’t care.

Seven years and coffee still drips cold because a new coffee pot is not in their budget.

Julie finishes the ‘E’, snips the string and ties it with a knot nurtured by these months of dedication. She turns her work out and smiles. Bless This Home it says bordered with a floral pattern and what William thinks might be bunnies playing leapfrog, but he isn’t sure enough to comment.

“It’s time we call this place a home,” she says and already William conceives of places to hide the piece once he rips it from the wall. The sentiment, however, he agrees with.

He agrees that a blessing is a fair request considering the hostile nature of a life—where birth and death are the only guarantees. Faith embodies a certain level of helplessness and what if not helpless is he? He accepts that a blessing might be appropriate—he’s extinguished every other possibility for Julie’s conversion. She is a mother already, happily stitching plans into white fabric so that they can be hung, adored, and regarded as the end result of love.

Though William acknowledges the desire for a blessing, he knows the impossibility of one. He sees it every day, working the attempts free from the streets with scrub brushes and exhausted muscles. He cleans the dead from the world and what’s one more child? Just another body that someone will one day have to clean from the road.

William lights a cigarette in the living room. “It’s not going on the wall,” he says and leaves before yelling starts, slamming the door behind him. Engine heat still cracks and wheezes from his van. He climbs in and tries to clean his mind of the child.

Chapter Three

Brackenwood is a town mortared by distance. Citizens use the word neighbor over friend. Whispers carry gossip and spilled secrets, but these neighbors rarely gather to celebrate openly. Parades and sporting events exist, but not as hyped events, instead as fodder for neglected community boards and discarded flyers. Conscious separation permeates every rigid nod, every quiet hello, like some historical founder dictated this world, and the scheme has sustained, passed from generation to generation.

The citizens embrace this seclusion, contentedly existing as dots gapped by miles of barren roads and dust and would remain isolated if not for the messenger pigeon hobbyist rings peppered throughout the county. Feathers blanket the sky during peak hours, settling to a sporadic streak mornings and nights. When William first arrived in Brackenwood, he took the birds as a sign of his potential morbid prosperity: vultures circling carrion. Soon, they became a sport for Willi

am, circling their own dead bodies.

The predictability of their flight patterns makes messenger pigeons an easy target. Not that William consciously seeks easy targets, but when something flies through an empty scope, ego steps in to pull the trigger. He studies a bird’s arc, its determined flight pattern. He squeezes enough time to set up a shot, take a few breaths. For a single moment the world moves around William and the bird. His is separate, pulled far from monetary engagements and doubt, fatigue and household concerns. All that matters is the pigeon and William and the inevitable.

William fought a childhood lisp. The terminology of speech therapists stays with him. They would call his shots noise—the interference along a communication channel interrupting an otherwise clear and articulated message. When parents scream at their children it creates a form of noise, the message grows bigger than the child’s willing comprehension. Beatings start. Bruises swell. Lives crumble.

Aiming at birds from a billboard fifty feet high along an unpopular highway leaving town from a desolate east side settles William the way eternal arguments with Julie can’t; those disagreements end always in a grey stalemate. From this high up the world takes on just two shades: trees and sky. The decisions are two: shoot, hesitate. The results are two: hit, miss. And the billboard, like all others, has two sides: eastbound, westbound.

The east side advertises a hand painted pro-life statement reading “Abortion Stops a Beating Heart” but the “Heart” is a faded drawing. From a distance it only reads “Abortion Stops a Beating,” and the sentiment is oddly reassuring considering the life span of a bird and the length William allows it to live. The other side, pro-military, a soldier standing at attention, proud and confident. No words.

The subtle afternoon simmers to its pinnacle. He pans the treetops, pulling to sudden movements. Dust maybe. Maybe a glare caught in the chipped paint at the tip of the gun’s barrel. Maybe a bird. He pulls out a cigarette and calms. He breathes slow enough to notice a westbound pigeon. The air warms, and a breeze tempts William’s nerves as he views the world through his shotgun. Though he wouldn’t shoot without confidence, the shots do stray. He takes a chance.

Stranger Will

Stranger Will